It is a great honor to have my book published in China. Thank you for beginning to read it, and I hope you enjoy the whole experience. In a sense, you are traveling to ancient Mexico and Central America and you will enjoy finding parallels between China and “Mesoamerica.” Both were among the world’s earliest civilizations. Mesoamerica has a rich history of indigenous cultural development that began with hunters and foragers over 10,000 years ago and over the centuries developed cities, states, and empires. Mesoamerica was transformed about 500 years ago with the European conquest of the Aztec empire of Mexico in 1521.

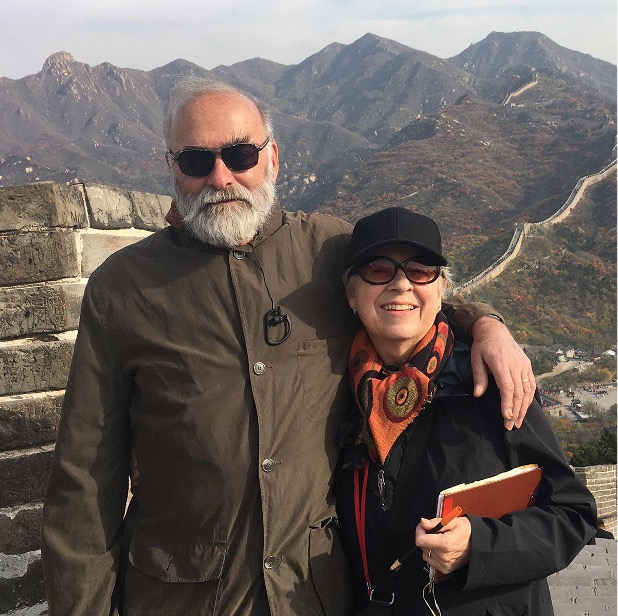

Empires, kings, monumental works – these essential features of Mesoamerica’s culture history have counterparts in China. And while Mesoamerica did not produce a massive structure that could be seen from space, like the Great Wall, its societies were organized in much the same way as those of China. As I stood on the Great Wall at Badaling a few years ago I was dazzled by this engineering achievement and thought about how it harnessed the labor of so many people: kings commanding construction; architects and geomancers who planned this immense project; diviners determining propitious days to begin the work and complete it; priests with their blessings; masons; workers quarrying and hauling rock; cooks and provisioners of food; cleaners and waste removal crews. If we had been there while it was being built we would have heard shouts and work chants, the sounds of stone being dragged into place and fill for the wall’s interior being dumped, and we would have smelled the woodsmoke of cooking fires.

The Great Wall at Badaling was built over 500 years ago. Contemporaneous with the Ming dynasty, the Aztec empire was flourishing in Mexico. It drew goods and labor from about 5 million subjects, from the Pacific to the Atlantic in provinces extending over 100,000 km2. The Aztecs are my scholarly specialty and I have studied their agriculture, their villages and cities, and their homes and palaces. Like Chinese palaces, Aztec palaces include administrative residences for ruling families, pleasure palaces at royal monumental gardens, and royal enclosures on pilgrimages and military campaigns. Palaces were centers of activity for all of Aztec society, and ruling families were cultured and literate. They collected tribute, kept records, gave feasts and led rituals. Aztec royal scandals mostly focus on power and sex, fascinating proof of the universality of human weakness.

I learned all of this in years of research after an unexpected find at a dig in the countryside not far from Mexico City. The village site of Woman-Palace extended over several hectares of pasture, with Aztec period pot sherds littering low mounds — the remains of houses abandoned in 1603. We excavated about a dozen of these mounds, and the largest by far covered the ruins of a building with the classic layout of a rural administrative palace (discussed and

illustrated in this book). I studied all the Aztec palaces I could find, those mentioned in old manuscripts and the few that had been explored by archaeologists.

The palace at Woman-Palace was tiny (625 m2) compared to the Aztec imperial palace of Montezuma in Mexico City, which covered 4 hectares but will never be excavated because its ruins underlie the National Palace of the Republic of Mexico – the conquering Spaniards claimed many choice pieces of real estate in and around Mexico City. Montezuma’s palace covers a large city block, but at that time in Beijing, the Ming palace, the Forbidden City, was much larger – 72 hectares.

In spite of the difference in size, the Forbidden City has much in common with Aztec palaces. Exploring the Forbidden City, I appreciated its beauty and the sprawling layout of courtyard-centered compounds. The Forbidden City was central to Ming conceptions of spatial organization and this was brought home to me when I visited Beijing’s Bell Tower and Drum Tower, due north of the Forbidden City, and realized that I was standing on a major chord of the city’s ancient layout.

So too was Mexico City divided into quadrants by its founders in the early 1300s. Many Mesoamerican cities are laid out to access sacred energy and to adapt to local conditions. Their temples are situated on top of pyramids, many of them built over royal tombs. Palaces are usually beside the pyramids. This book includes many plans, photos, and drawings illustrating how Mesoamericans developed their communities, and also the tools they used and decorative pieces that were objects of great beauty, especially those worked in jade.

You will discover much in reading this book and enjoying its illustrations. Its beauty was created by a team of editors and designers at Thames & Hudson publishers (London and New York). My editor at Thames & Hudson, Colin Ridler, was instrumental in producing a work so superior that it received the 2005 Book Award of the Society for American Archaeology, the only time the award has been conferred on a book covering one of the world’s major culture areas for all of its indigenous history. The book is presented here by Sanlian publishers (Hong Kong), with a translation by Li Xinwei, Ph.D., Professor of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and a specialist on the archaeology of the Maya of Mesoamerica (about CE 600-900, the time of the Tang dynasty). We have all worked to ensure that you will find Mesoamerica a worthy place to explore.

With my best wishes, Susan Toby Evans

Pennsylvania State University